Thea Energy previews Helios, its pixel-inspired fusion power plant

Fusion power has the potential to rewrite trillion-dollar energy markets, but first, startups have to prove their designs will work and won’t be too costly. Neither is easy, especially when considering the massive magnets and lasers used in many designs must be installed with millimeter precision or better.

Fusion startup Thea Energy says it’s pixel-inspired reactor and specialized control software should be able to generate power without requiring the same level of perfection.

“It doesn’t have to be as good to begin with,” Brian Berzin, co-founder and CEO of Thea Energy, told TechCrunch. “We have a way to tune out imperfections on the back end.” That margin of error could give Thea a leg up on the competition.

Fusion power plants promise to deliver gigawatts of clean power to the grid, but material and construction costs threaten to make them uncompetitive with cheap solar and wind. By building a power plant first and ironing out the kinks in software, Thea could help bring the cost of fusion power down dramatically.

But first the company has to build a working prototype. Today, Thea is publishing the details of its design, including the details of the physics that underpin it. The startup shared the paper exclusively with TechCrunch.

Thea is building a unique take on the stellarator, a specific type of reactor that uses magnets to whip the plasma fuel into shape. Magnets are one of the two main ways that fusion scientists keep plasma heat and confine plasma until fusion reactions occur. The other, known as inertial confinement, uses lasers or some other force to squeeze small fuel pellets.

Most stellarators are built with magnets that look at home in a Salvador Dali painting. But Thea’s design uses a dozen larger magnets and hundreds of smaller ones to create what you might call a “virtual” stellarator.

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

October 13-15, 2026

In a typical stellarator, the magnets are built to follow the contours of a shape that’s intended to work with the quirks of plasma, helping to confine it for longer using less power than tokamaks, which use a series of identically sized and shaped magnets. Yet stellarators have one major disadvantage: the irregular shape makes mass manufacturing magnets challenging.

So instead, Thea designed its reactor around small, identical superconducting magnets that are arranged in arrays. The startup will use software to control each magnet individually to generate magnetic fields that can replicate a stellarator’s wobbly shape.

The approach has several upsides. For one, it has allowed Thea to rapidly iterate on its magnet design. In the last two years, the company has tweaked the design more than 60 times, Berzin said. “Most fusion companies, you’re dealing with magnets that are the size of a car or a laser the size of a car or a wedge the size of car. That unfortunately means one is $20 million and takes two years [to make],” he said.

It has also meant the company can use software controls to overcome any irregularities in the way the magnets were made or installed. To test its original control system, Thea built a three-by-three array of its magnets laced with sensors. The controls, which were derived from the physics of electromagnetism, worked well. But the company also wanted to see how AI might handle the task, so it also trained a new one using reinforced learning.

The team came away surprised at how well it all worked.

“We purposefully threw curveballs at the array,” Berzin said. “We purposefully dismounted a magnet by literally over a centimeter. You could see it was super out of line. It was really hard for us to actually manufacture it so poorly.” The team also tested superconducting material from five different manufacturers along with intentionally defective material. “Every single time we did that, the control system, without us turning knobs and intervening, was able to tune out those defects,” he said.

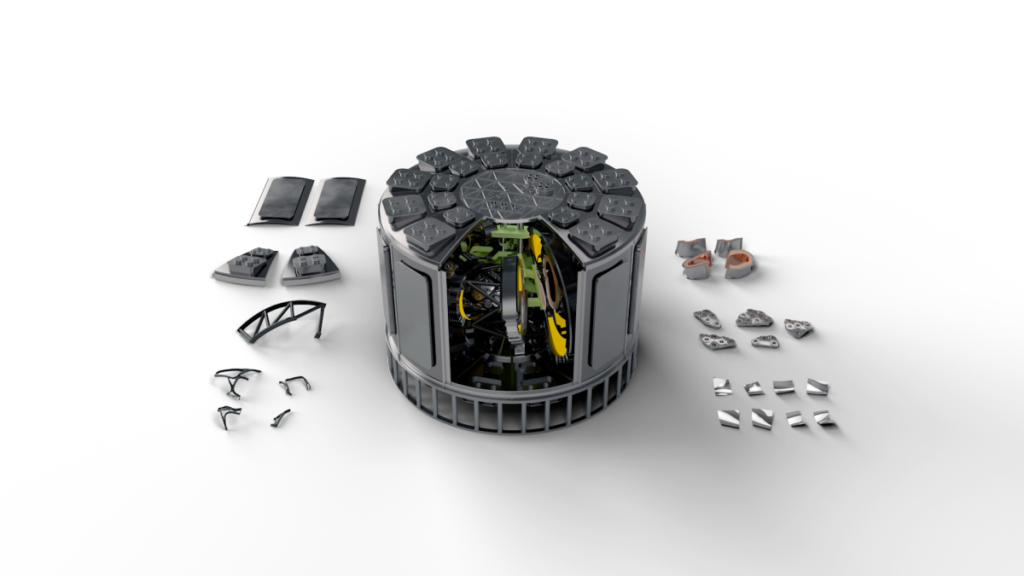

Thea’s reactor design, Helios, will use two types of magnets. One the outside, 12 large magnets of four different shapes will do the heavy lifting to keep the plasma confined. They’re similar to those found on a tokamak, the type of doughnut-shaped reactor that competitor Commonwealth Fusion Systems is building. Inside the large coils, 324 smaller circular magnets will fine tune the shape of the plasma.

The startup predicts Helios will generate 1.1 gigawatts of heat, which a steam turbine will turn into 390 megawatts of electricity at a cost below $150 per megawatt-hour. The reactor will have to shut down for an 84-day maintenance period once every two years. If all goes well, that means its capacity factor — a measure of how much power it generates over a given period of time — will be 88%. That’s far better than today’s gas-fired power plants and almost as good as today’s nuclear power plants.

Helios is still in the conceptual phase. Thea first has to build Eos, its initial fusion device that’s intended to prove the science behind the concept. Berzin said the company will announce a site for Eos in 2026 with plans to turn it on “around 2030.”

As it builds Eos, Thea plans to start work in parallel on Helios. It’s a similar approach to how Commonwealth Fusion Systems is moving forward with work on Arc, its first commercial power plant, while building Sparc, its demonstration plant.

For now, Berzin is looking forward to hearing what the fusion community thinks. “This is the release of the overview paper. This will be followed up by quite a substantial amount of work that will come out via peer review and publication,” he said. “Now is the moment for us to go and set up the partnerships, collaborations, get the end users engaged to go build the first one.”